Measure your rental property’s income success

Is your rental property a B league player, or a star performer? Measuring its performance will help you to decide what to do next: sell it and buy something else, take out equity to buy another – or, at the very least, have peace of mind that the figures do stack up.

Doing these sums is a key part of creating a business plan. Before we dive into the maths to help you do that, a quick note: apart from stamp duty, tax is not included here. Because tax is so specific to your individual circumstances, it’s impossible to account for it in these generic formulae.

Measuring income

There are three simple ways to measure income success, each useful in a different setting:

Gross yield

If someone talks about ‘yield’ without saying which type, they usually mean gross yield. This is the yield before you’ve taken any costs into account:

What is a good yield? As a rough rule of thumb, once you’ve accounted for costs, you’ll struggle to break even on a gross yield under 4%. For a better income, look for a gross yield of 7%–9%.

You’ll hear the term ‘yield’ thrown around a lot if you’re looking at buy-to-lets. Be aware, though, that many people misunderstand what it means, or even deliberately try to mislead you with glossy yields. Do your own sums.

When it’s useful. As a rough-and- ready shortcut to compare properties that are likely to have similar running costs, like two modern flats.

Net yield

To be more precise, factor in your running costs. Net yield takes into account mortgage interest, agent fees, repairs, service charges, insurance and loss of income when the property is empty – all of which we’ll cover in more detail later. If a seller quotes you a net yield, do check what they include so you can compare like with like.

When it’s useful. To compare properties that have different running costs – a flat and a house, say, as long as you can accurately estimate the expenses.

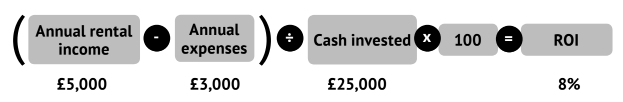

Return on investment (ROI)

In the net yield calculation above, 1% sounds like a paltry return. Why bother with tenants and tradesmen if you can just as well stash your cash in a savings account? Crucially, though, the cash wasn’t all your own – you borrowed much of it from the bank. Enter the power of leverage.

If you have a mortgage, calculate the yield based not on the purchase price, but on how much of your own money you invested:

Ta da! Suddenly all the bother seems worth it.

To get the whole picture, under ‘cash invested’ add all purchase costs to your deposit: stamp duty, surveys, legal and mortgage fees.

When it’s useful. To see how hard your money is working not just compared to other properties, but also to other asset classes. ROI helps you decide whether to invest in property, stocks or cash.

Measuring growth

When you’re buying a new property, stick to the three income calculations above to compare options. Even if you’re buying with growth in mind, there’s no way to predict what future growth will be. The only certainty is that it will differ from what you expect.

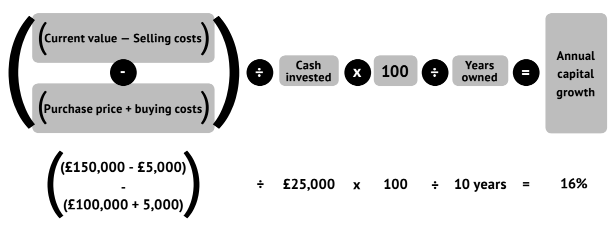

However, if you are deciding whether to sell or keep letting out your existing home, you can take its past capital growth into account:

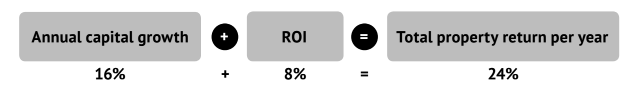

You can then use this annual capital growth to work out your total property return:

Pffft, try to beat that with a savings account. Yet before you crack open the champagne to celebrate your paper profit, bear in mind that it’s just that until you actually sell. Before then, its increase in value is pure theory; ultimately it will be worth what a buyer pays for it.

The Accidental Landlord

In the post-Brexit world of jittery prices, tax changes and 140-plus landlord laws, this Amazon bestseller tells you how to let out your own property with complete peace of mind.

Get free help